Post-Agentic Code Forges

A commentary on whether GitHub and GitLab is ded-ded, or alive-ded

I got nerd snipped by Thorsten Ball recently.

If you missed it, he recently posted a short video commenting on whether GitHub is still alive in a world where coding agents are widely adopted. Here is the transcript

Well, since I have spent countless hours in the last 2-3 years sketching a plan to replace GitHub and GitLab, I obviously have a take on the matter. So let’s dive in.

Monorepo and Mergeability Checks

With coding agents, there is a need to build the context to improve the result. Turns out, it’s really easy to get an accurate context when all of your code is in one single repo. Just a single working copy, no version drift between workspaces, no “superior manifest” of multiple repos patched together to make a virtual workspace. So naturally, monorepo adoption increased.

But if you spend time talking to the AI labs, I think one thing you should ask is if they felt the pain of when using a high velocity monorepo on GitHub or GitLab: the mergeability checks (merge-check for short).

Mergeability check is a check these code forge services often run to check if your Pull Request (Merge Request on Gitlab) has any conflicts with the target branch. It’s triggered often, I’m pretty sure Gitlab used to trigger it whenever an MR was opened in the WebUI recently, or when a new change was merged into the default branch. The check happens by GitHub or GitLab attempting to create a merge commit, annotated with a hidden merge ref, in the repo storage.

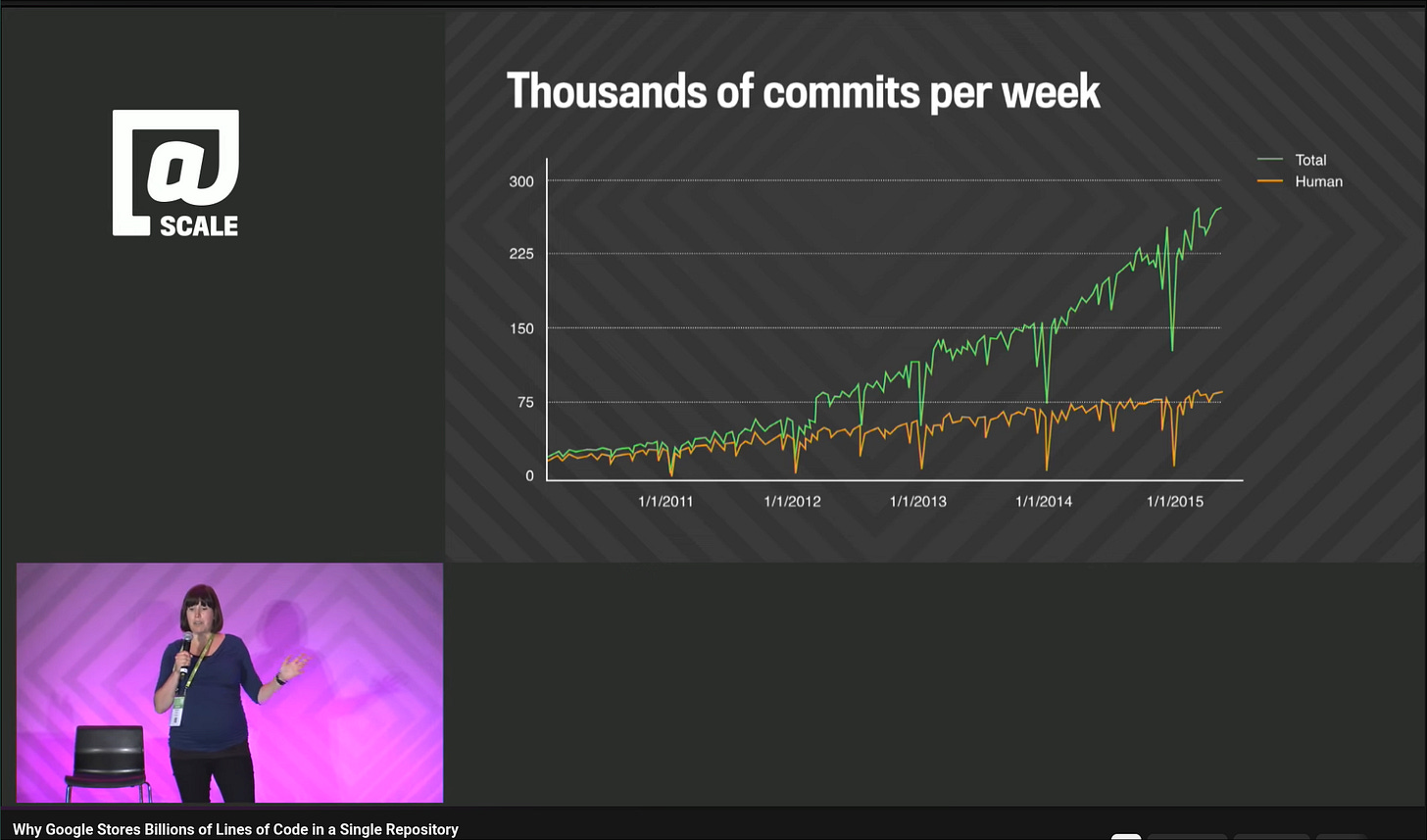

But in a post-agentic world where you have thousands of coding agents landing changes per hour, the default branch becomes an information highway that’s constantly invalidating all the merge-check results. Running merge-check becomes computationally expensive, even though the most recent merge-ort algorithm has already improved this by multiple factors.

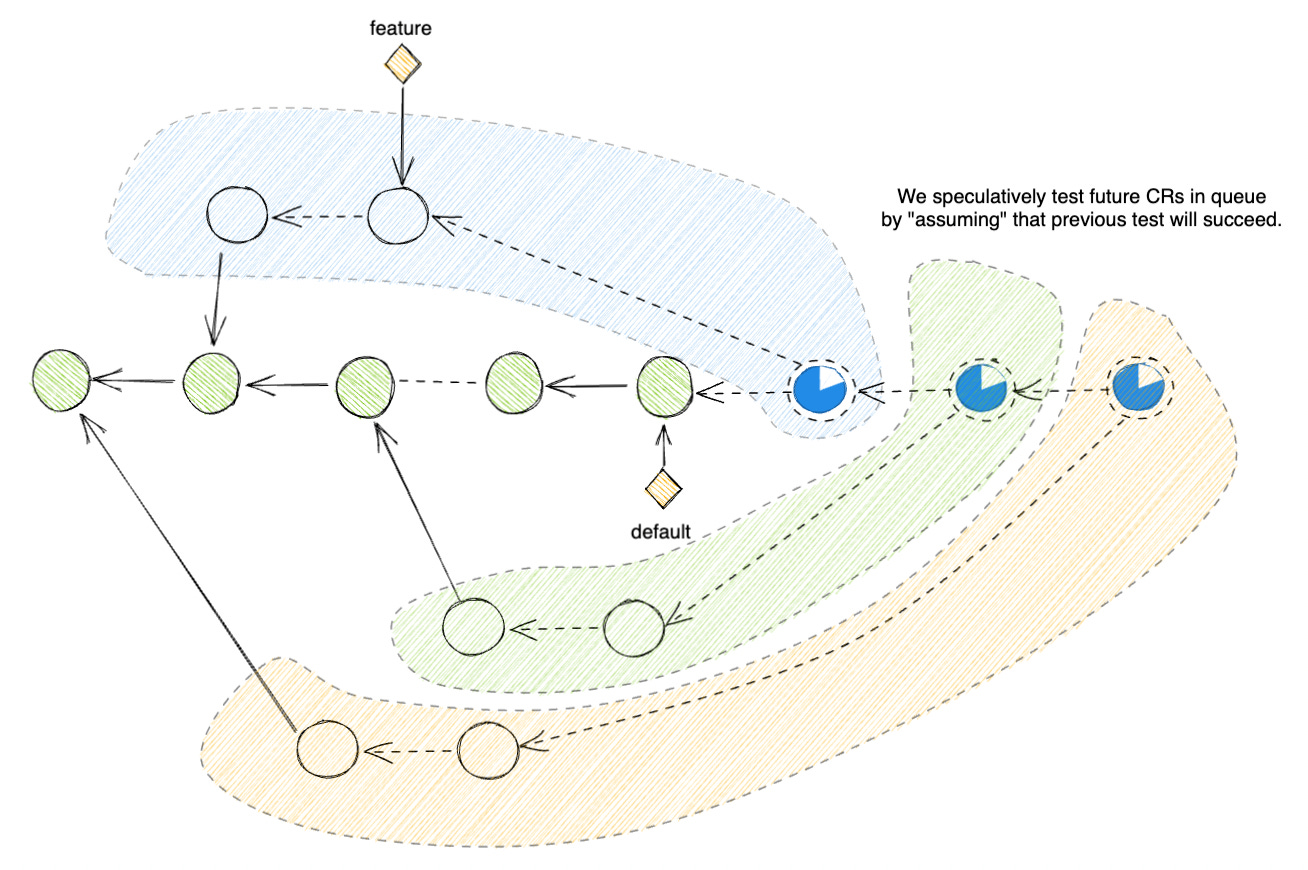

Worse, code forges often block the merge button when the merge-check result is stale. As a result, fast-moving monorepos have to completely abandon the PR workflow and replace it with a merge-bot account that has permission to push directly to the main branch. The bot will often get equipped with its own merge queue and speculative CI engine to speed up the process.

So a solution to this problem does exist. But imagine paying tens of thousands of dollars to a code forge service monthly just to build half of the most important feature yourself… It does leave a sour taste in the mouth.

Code Review

As the reliability of the coding agents increases, people will trust the result more and more. At one point, it will no longer be possible or efficient for a team of 10 human engineers to review all the changes from 1000 code farm agents running 24/7.

I think code review, as we know it today, will disappear. We should be teaching agents to work in pairs instead: one does the coding, then yields the result to a reviewer agent to judge whether the change is ready to queue for merge. Results are grounded by tests, a lot of tests. unit, integration, e2e, you name it. But human review in the hot loop is no longer economically viable.

So one would take a step back and think: what did we use code review for pre-agentic coders? What problems did it solve?

I can think of the main 3:

Increase code quality.

Increase code ownership, decreasing the “bus factor”.

Compliance checks.

In a post-agentic world, 1-2 are gone. As the models and the harness wrappers(coding agent cli / orchestrators) increase in reliability and quality, code quality goes up. You would not need to worry too much about the bus factor then, because the agent can quickly analyze the problem and fix it. It would make more sense if we just ground all of the coding outputs with actual automated tests that reflect the expected product flow and let the agents do their thing, relentlessly and quickly.

However, compliance checks won’t go away. The compliance and regulatory framework will still be there, slow to evolve. In these cases, a human reviewer is still a must.

But there is a trick: move your review step to a pre-release stage instead of gating it at pre-merge. Give your agents their own default branch (i.e., “bot-main” instead of “main”) if needed. Before checking our deployment tag/branch, or before merging all of their changes to the real ‘main’ branch to trigger a deployment, cook up a UI to help the human reviewer go through all the changes quickly. The review workload will be big in this case, so give the human check boxes and group those check boxes in smaller categories for easier review. You can also make it an “LLM-assisted” review (i.e., have the agent explain the change to the human reviewer), but the human still needs to be responsible for clearing all the checks and hitting the deploy button.

If your business is not subjected to any regulatory compliance framework like this, well, good for you. But I know there is a lot of money on the table for this feature, and none of the code forges move fast enough to realize this.

Testing and CI

The biggest change in the post-agentic world will be testing. Agentic changes will need to be grounded and verified by tests. Having tests vastly improves the agent outputs, just like having real code references improves the agent's chain of thought.

But ALL the traditional CI systems are slow, bloated, and are a waste of compute. Historically, when an organization reaches a certain scale, it naturally hits some of these problems and has to converge toward one solution: hermetic build tools.

Google did it first with Blaze. Meta(Facebook back then) reached there soon after and started to create Buck. Twitter (now X) also reached that stage and started Pants Build.

These tools eventually evolved into Bazel, Buck2 today, powering the majority of the big tech names: Apple, Stripe, Nvidia, Tesla, SpaceX, Robinhood, … From software to hardware, from cloud computing to social networks, from financial institutions to self-driving and robotic. The engineers all agreed on the same thing:

With reproducible builds, you can cache + reuse results and save on compute.

To cache things accurately, you need to build the cache key from a Merkle tree of all factors that influence your task: inputs, env vars, tools, args, etc…

With reproducible builds, it should not matter if you run the build on your laptop, your workstation, or a cloud workstation.

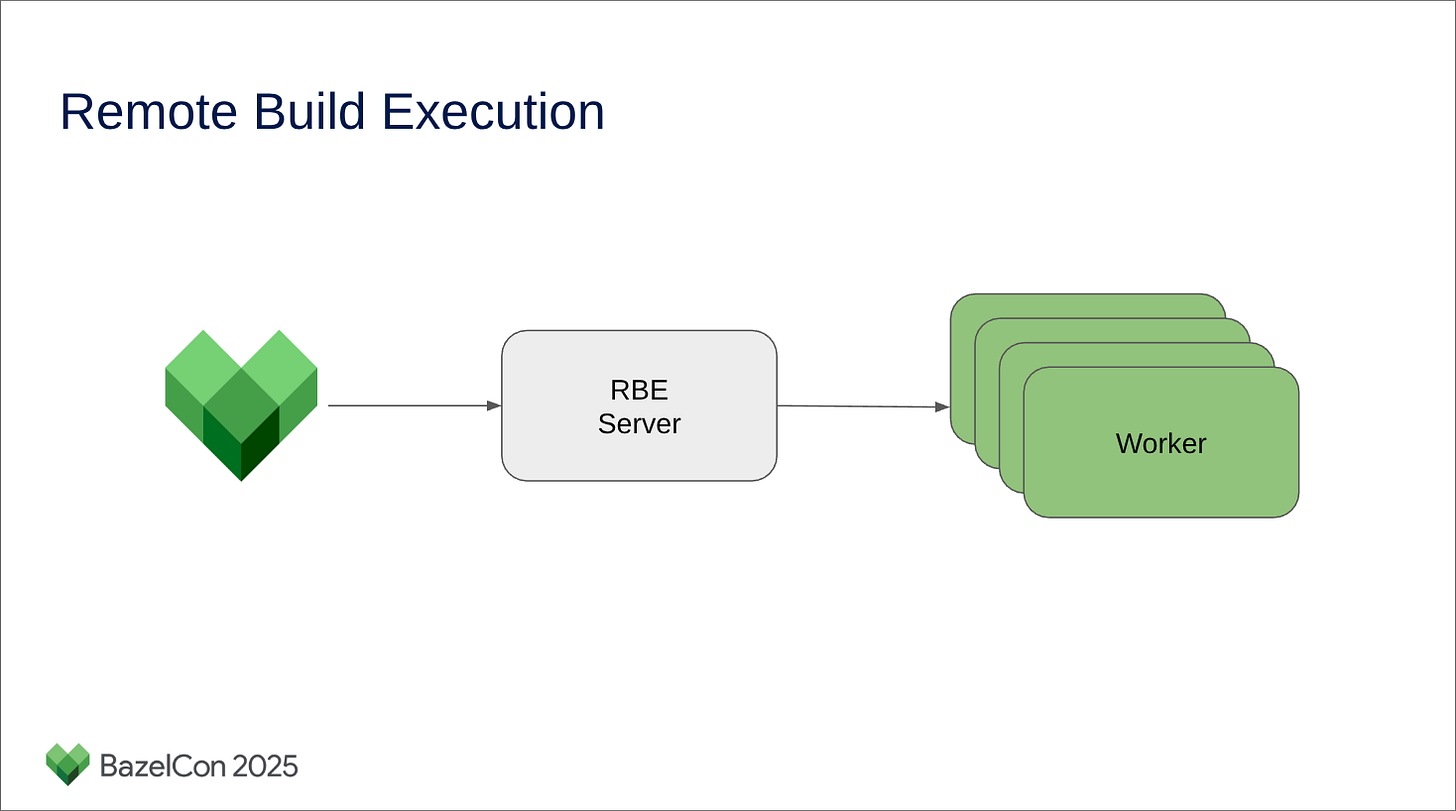

If you divide your build into many smaller reproducible tasks, you can distribute these tasks to a build farm and use the aggregated result.

This is exactly what tools like Bazel and Buck2 do out of the box for you, with additional telemetry and profiling goodness on top.

But Son, what does this have to do with Coding Agents?

Well, the new thing here is that the Big Code problem is no longer exclusive to Big Techs, like it was in 2016, nor is it exclusive to multi-billion-dollar companies, like it was in 2020. The Big Code problem, powered by coding agents, is now accessible to everyone.

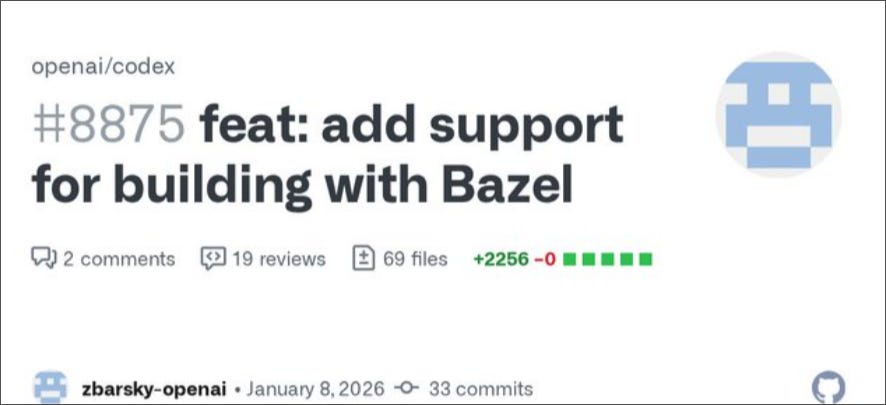

If you have yet to notice, many of the big AI labs started to hire a lot of experienced Dev Infra folks recently. Many of whom have years of experience in migrating monorepos onto Bazel, deploying Cloud IDEs, and setting up distributed build farms for Big Tech companies. The most notable hint would be that Codex started to adopt Bazel as a build tool.

And if you check out the commentary on these Bazel PRs, you can easily note the impact Bazel has on the future Code Farms’ performance.

Because of the remote caching benefits we get from BuildBuddy, these new CI jobs can be extremely fast! For example, consider these two jobs that ran all the tests on Linux x86_64:

Bazel 1m37s …

Cargo 9m20s …

From Codex’s PR #8875

… as OpenAI is generally using Bazel internally for many projects

From Codex’s PR #8504

Meanwhile, most code forges are stuck in the old world, with hundreds of CI jobs re-running unconditionally for each change landed on master. No granular build graph invalidation, no confidence in the test quality, and computationally expensive to scale up for monorepos with more than 100 active users.

Others

I have other quick thoughts on the death of existing code forges as well:

Coding agents do not need file system snapshots. They need a lot of commits and automatic commit push to the cloud. If you have not yet watched Durham Goode videos (some on YouTube, some on Facebook videos) about how Meta designed and scaled Mecurial with push-rebase extension and Commit Cloud service, go watch them. It’s a great product roadmap to scale up forges in general.

High velocity merge queue will need a shared conflict-resolve cache. In Git, this would be git-rerere cache, but distributed. In Jujutsu, I think the resolve is stored inside a commit’s header? But the ability to freely reposition commits within a queue, batching stacks of commits, can result in huge CI compute savings and speed up the agentic loops.

I have yet to explicitly state this, but Code Farm, just like Build Farm, will be a thing. Instead of headful cloud workspaces exposed to the IDE, we will now have headless cloud workspaces exposed to the agents. Similar constraints, but bigger scale and easier to manage (because unlike a human engineer, agents will not mistaken the cloud workspace is a local shell and start to install Dota 2 on it, causing disk space issues). Although prompt injection attacks are definitely a harder category to defend against.

As the CI workload increases, code forges and CI services will have to prepare ways to distribute the code changes without causing significant pressure on the git storage layer. We can see GitLab is struggling with this as it tries to revamp my 6-year-old feature request for sparse-checkout support, as well as introducing a new layer of pull-through caching proxy. Canva built this a while ago by forking google/goblet to add Gitaly’s pack-object cache on top. I suspect we will continue to see more of these in a post-agentic world: from a multi-tier git cache setup (local disk - local network - global) to a p2p sharing distribution system similar to Sapling’s Commit Cloud.

Don’t even get me started on Git LFS.

Housekeeping Notes

I don’t have much time to draw up pretty diagrams, so I pulled a few of them from my previous blog series. As HashNode began to block all bots and automation using CloudFlare, the RSS feed there is no longer functional. I am planning to migrate that blog series over to Substack soon and bring everything under my own domain for easier migration in the future.

So if you are interested in these topics, subscribe and stick around.